Fifth Chotarian Empire

Fifth Chotarian Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 586–1052 | |||||||||

Chotar V at its greatest extent, 981 CE | |||||||||

| Capital | Kozrat | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Lacrean, Late Chotarian (ritual) | ||||||||

| Religion | Ishtinism | ||||||||

| Government | Hierocratic rescapitan monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 586–610 (first) | Čiron | ||||||||

• 1046–1052 (last) | Lēl VII | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Coronation of Čiron | Estion 5, 586 | ||||||||

| Metrial 10, 1052 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 981 | 3,700,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Chotar | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series | |

| First Empire (c. 1600–1030 BCE) | |

| Dark Age (c. 1030–760 BCE) | |

| First Interdynastic (c. 1030–930 BCE) | |

| Ukmai Empire (c. 930–850 BCE) | |

| Second Empire (c. 930/760–359 BCE) | |

| City and Kingdom era (359–220 BCE) | |

| Third (Urumen) Empire (220–54 BCE) | |

| Third Interdynastic (54 BCE – 58 CE) | |

| Fourth Empire (58–324 CE) | |

| Equinox era (324–586) | |

| Fifth Empire (586–1052) | |

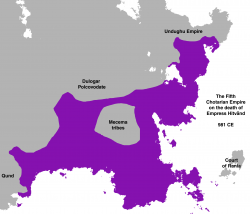

The Fifth Chotarian Empire was the last, best-attested, and most powerful of the classical Chotarian empires, existing for half a millennium from 586 to 1052 CE. In the Fifth Empire period, Chotar attained the height of its territorial expansion, encompassing most of Outer Joriscia as it extended to the borderlands of the modern Lutoborsk in the north and across modern Anabbah to Petty-Lestria in the west. The empire thus left numerous legacies, and despite the great changes that would follow its collapse, many of the features of later Outer Joriscian society find early prototypes in this period, including the Chotarian slave-priesthood for the later rabtat and Scholars; and the empire's substantial corpus of regulations of individual behaviour for early zaconic law. More explicitly, Lacrean nostalgists in the 18th century and their neo-Chotarianist successors would draw primarily on images of the Fifth Empire in their reconstruction of the Lacrean state from the Chotarian Restoration of 1778 up to the dismantling of the Sixth Chotarian Empire in 1958.

The basic government structure of the Fifth Empire was established in the opening decades of the empire, drawing on the highly autocratic theories of the Peribolasts of the late Equinox era, and was notably different from its more ancient predecessors in the unprecedented scale of the authority it exerted over the empire's society and economy. Its birth was marked by hard-fought conflicts between the newly restored central court and the hereditary monarchs and aristocrats who had risen to power at the end of the Fourth Empire. The result of these wars was the Chotarian census and the consecrated land system, in which all land was treated as property of the state apportioned by temple administrators to immediate holders on a temporary basis, and a strict maximum was imposed to prevent the return of a hereditary aristocracy. In the place of the ancient provincial governors-turned-nobles, the new office of fejedelem was created to oversee subsidiary temple-courts in large new provinces termed circuits, where they would be both representatives of, and responsible directly to the emperor.

The Fifth Empire also marked the peak of Ishtinist religious practice, which was rendered into a potent instrument of autocratic rule. The Ishtinist priesthood, which had grown increasingly autonomous over the preceding centuries, was folded tightly into the imperial administration and expanded into a large caste of temple-slaves, administering a hierarchy of city temples concentrated at the temple-courts of the emperor and his fejedelmek. Cultic practices were reformed, standardised, and revitalised to assert the emperor's divinity and ultimate supremacy over all human life. The supreme temple-court at Kozrat was divided into a number of specialist bureaucratic departments to assist the emperor in governing his sprawling realm, and at the local level priests charged with the administration of the census were responsible for fine-grained supervision and discipline of individual household units. Drawing on the cultured Chotarianised elites in the provinces, the reformed Ishtinist hierarchy could thus extend and profoundly deepen the reach of imperial rule.

Over its long life, the Fifth Empire faced numerous internal and external challenges. The most serious of these were the crisis periods of the Schism in the North of 728–60, in which the empire temporarily fragmented into competing imperial courts and threatened to collapse entirely, and of the middle of the 10th century, in which it was faced by provincial rebellions, most prominently the Revolt of the Gergote Courts (950–66), and the devastating Yassan plague. Both these crises saw changes in the empire's social structure and the introduction of important economic and administrative reforms, which abetted a general trend of increasing centralisation that continued until the empire's demise. Though it enabled the Fifth Empire to flourish as one of the most sophisticated societies of its day, this high degree of centralisation ultimately proved the empire's undoing, and the Secote conquest of Kozrat in 1052 triggered a cascading collapse of the imperial administration, causing the end both of the empire and of classical Chotarian civilisation itself. Even before the Secote conquest, however, the empire was confronted by powerful external rivals: aside from the perennial threat of nomadic incursions from the Joriscian steppe, the empire was bordered to the west by the Qundi kingdoms, and to the north by the Undughu civilisation in modern Lutoborsk and Kiy. The copiously preserved administrative records of the Fifth Empire render the period in which these cultures coexisted a golden age of classical diplomacy.

While Chotarian was dead as a spoken language by the time of the Fifth Empire, it survived as the empire's language of liturgy and written administration, and the ancient Chotarian writing style of cuneiform—though rendered anachronistic in form by the general replacement of clay tablets by paper—continued to be used in these contexts until the empire's demise. The shared spoken language of the empire and its elite culture was Old Lacrean, the direct ancestor of the modern Lacrean language; with the common adoption of the Chotarian alphabet for the transcription of vernaculars, however, numerous other dialects of Neo-Chotarian and other linguistic origins are also attested in this period.

| Preceded by Equinox era 324–586 |

Chotarian history Fifth Empire 586–1052 |

Fall of Chotar |