Helminthasse

Alliance of Independent Siur Commonholds Բամդալագիձ Օհաթւմ Սիւրսքւմ Վիձալդւմ Bandalagið Óháðum Síurskum Viðaldum | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Լատա Ալդրեի Սիգ Láta Aldrei Sig “Never Let Up” | |

Helminthasse (in yellow) within Messenia | |

| Capital and largest city | Virkið |

| Official languages | Hártal |

| Demonym | Helmin |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

• Althein | Ásgeir Stórlind af Hydrædsdali |

| Lilja Vestan | |

| Establishment | |

• Establishment of commonhold of Helminthasse | 12th century CE |

• Unification of Siurskeyti | 1623 |

• Secession of Helmin commonholds | 7 Petrial 1812 |

| Area | |

• Total | 304,561.6 km2 (117,591.9 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Census | 26,801,469 |

• Density | 88/km2 (227.9/sq mi) |

| Currency | Kammur (HEK) |

Helminthasse (Hártal Հելմինթասսը, Helminþassi), officially known as the Alliance of Independent Siur Commonholds (Բամդալագիձ Օհաթւմ Սիւրսքւմ Վիձալդւմ, Bandalagið Óháðum Síurskum Viðaldum), is a nation in western Messenia. It borders Vernland, Arakan and Tvåriken in the north, Vettermark, Västrahamn, Grand Fenwick and Elland in the east, Alcasia and Soeria in the south-east, and Siurskeyti in the south and west, with a short coastline on the Medius Sea in the north-west.

As an independent nation, Helminthasse is only latterly into its third century of existence, having been created as a result of the secession of five of the constituent commonholds of Siurskeyti in Petrial 1812, an act cemented by the short-lived Summer War of that year and confirmed by the Treaty of Fensbrú, signed in Nollonger of the same year. Having inherited much of its political structure from its southern sibling, the country is, like Siurskeyti, an elective monarchy, with its ruler or althein appointed by, and usually from among, the rulers (theins or þeinar) of the five commonholds to a fixed five-year term of office.

Etymology

The familiar name for the country, Helminthasse, derives originally from the Siur commonhold of that name, which is located in the west of the modern country; Helminthasse was the prime mover in the secession dispute, and its name became attached to the wider Alliance by a process of metonymy. This name in turn derives from that of the Helminn family, members of which established the original commonhold in the twelfth century out of smaller and more scattered holdings, tenure of which can be traced to the early eighth century in places. The derivation of the term thasse is uncertain; while there are clear similarities with the Siur lesser noble title of thosse (þossi), it is thought to emerge from Proto-Siur þasi, "cohort" or "regiment" (ultimately from Antissan dassu, "strong"), and presumably thus indicative of the Helmin's fighting strength.

Physical geography

Most of Helminthasse, traditionally identified as the region of Vossaria, is dominated by highlands, contributing in part to the country's relatively low population density. Flatter terrain is present on the coast and the Halðamar river valley. The eastern regions of the country are more mountainous, including the central Sarlhamar range and the larger Aphrasian mountains of the eastern borderlands, extending into Elland, Vettermark and Grand Fenwick. The country's highest peak, Maldafell, lies close to the point at which the Helmin border meets those of the latter two countries.

Helminthasse's longest river, the Esker, rises in the Aphrasians and forms part of the border with Elland before passing through the south-eastern regions and into Siurskeyti, where it enters the Harsirflói. The Halðamar with its main tributary, the Levanð, lie in the north, with the former marking the border with Tvåriken and Arakan. Other significant rivers are the Ekna in the north-west, the Tarsa and Teþar in the south-west and the Þarkur, which forms part of the border with Alcasia.

History

Prehistory: the wild west

The first known inhabitants of present-day Helminthasse were the Neolithic Vítrör people of the coastal regions. Many of these people were driven north and east by intrusions from the south, giving way to the Jötunsteinn culture of the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. The later Jötunsteinn were attacked by, and to a large degree absorbed by, the invading Dammurites, a late Bronze to early Iron Age people of the south-western regions (within present-day Zeppengeran); the cyclical waxing and waning of Dammurite hegemony saw most of the Siur lands pass in and out of their control between roughly 1800 and 1200 BCE; the Antissan culture of which Dammuri was one of the leading exemplars, left a clear mark on the indigenes; in particular, Thúrun, the native faith of the Siur country, took on some substantial colouration from the southerners’ Palthachism. In the north-west there was some degree of contact with the Sabāmani by way of the trade conduit today known as the Tin Road.

The fall of the Dammurites’ Larhine Empire and the flows of population into the region in the late ninth and eighth centuries caused massive upheavals in the far west. The northern empire fell to tribal invasion, including the return of the Vítrör, now known as the Vossar, and was lost. The Vossar incursion became the seed-bed during the early eighth century BCE for a number of small states, most of which ultimately coalesced into the Kingdom of Vossar (c. 700–250 BCE), the largest single polity to exist in the region until the foundation of Siurskeyti more than two millennia later. The south was less unified, with a number of petty statelets being formed from the remnants of the Larhines and the western Sunneni, who settled in the region during the early fifth century BCE after a long drift west from their ancestral lands in the south-western steppe. Their gradual coalescence into the Siur – a term derived from the sieve-baskets used for fishing in the coastal regions (Hártal síur, singular sía) – was probably complete by the beginning of the Common Era.

First millennium CE: clash of arms, clash of faiths

In the first few centuries CE the Sunnic coastal regions were pulled more into the commercial mainstream of the Median rim, with the establishment of trading outposts of the then-powerful Neokos Empire bringing greater prosperity, along with a leavening of the Neokos’ Siriash, which held a small and determined presence despite the disapprobation of Thúrun priests. The wilder north country west of the Aphrasians had to contend with an expanding Third Sabāmani Empire; and although the invaders were beaten back at the Battle of Hydrædsdalur in 485 – the empire gained a certain degree of influence in the north-west. In the process it seeded its native Cairony; the faith is still a strong presence in Ærlasse today.

With influence from beyond the mountains steadily eroding the old verities of Thúrun, the times were ripe for a reappraisal; and this came in the early seventh century as the philosopher and jurist Ragna Hrafnamaður expounded the ideas now collectively known as Arlatur. Fiercely resisted by Siur leaders at first for its anti-authoritarian stances, it slowly gained acceptance at all levels over the period between 750 and 900 CE, driving Thúrun into the margins.

Drifting out of the world’s mainstream as the Neokoi and the Sabāmani weakened, the Siur commonholds were brought to unprecedented unity by the threat of invasion by the Secote Dominion in the late eighth century, electing a single leader; Jukka af Essingi, the thein of Myvatn in what is now northern Ærlasse, became the first thár of the Siur in 798. Generally agreed as the best military mind of the period, Jukka led the Siur in an extended war against the Secote from 805 to 808, forcing the invaders into stalemate and tactical retreat. Jukka died in 828, and the death of his successor Skjöldvaskur af Norðursundi six years later broke this fragile union, but his sterling example helped to consolidate his Arlaturi beliefs in the Siur lands.

1000-1650: business as usual during altercations

In the end, though, Jukka had only bought time for the Siur; the second Secote invasion in the tenth century was much more successful, and the Siur were overrun by the Secote Empire despite heavy resistance. The kunentsys imposed on the Siur during the Years of Bloody Hands are today remembered for their harsh treatment of the locals, especially in the western Aphrasian highlands where they tried to use local grasslands as pastures for their nomadic lifestyles. Their repression of Arlatur as a potential focal point of resistance to their rule was at times savage; but the Secote, often loosely Sirian themselves, likewise stamped hard on Sirian variants in the south and pushed the small Siur Cairan communion onto the sidelines. As time passed, though, even their own faith weakened, with many kunentsys, whose Sirian identity was always worn lightly, adopting Arlatur as they assimilated into local nobility; and as the Secote Empire crumbled away in the early twelfth century, Siur culture began to reassert itself.

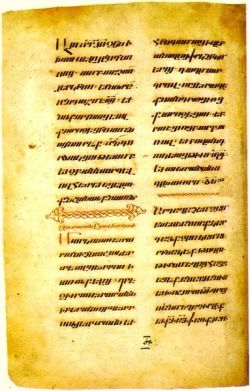

But re-emergence from under the Secote yoke did nothing to unite the Siur; still individually weak, the commonholds feuded regularly, at varying levels of intensity, and a political map of the Siur lands resembled, as some have put it, “a patchwork quilt sewn by a drunken needlewoman”. Alongside this, though, the post-Secote Trying Times were also an age of expansion of learning, and the period of the first flowering of written Siur culture, in which the great sögur of the past were first committed to written form, while the various expansions of and commentaries upon Arlaturi teachings were brought together and codified. The Siur commonholds also shook off the focus on the continental interior forced on them by the Secote to look outward to the sea; the targets of regular pirate raids from the islands of present-day Tassedar and the eastern Sabhian Unity in north-eastern Ascesia, the Siur were driven to develop their own seafaring capability in response. Attempts at trade in Sabhian waters were moderate, but they later expanded into the western Medius Sea littoral with markedly greater success. Of the northern commonholds, Lágskáli – known as Sarevi after 1556 – was most prominent, with the city itself having a leading role in the mercantile Tolvic League.

However, the threat of unsettlement and open warfare was a regular undercurrent; the doctrinal split in Arlatur now called the Vinadeila ruptured the country for some fifty years, and a complex weaving of alliances and favours dragged most of the north into the War of the Teþar between Vonskil and Skjóll between 1584 and 1590. Outside the region, competition from a resurgent Odann and the emergence of Joriscian combinations in the Medius were hampering the Siur commonholds’ claims to dominance there. Then, in the first decade of the 17th century, the spectre of Seranian fever came to stalk the Siur country, with a horrendous death toll over the period 1606–07.

But even in the worst darkness there is light; the new generation that came to the fore after the fever passed would change the Siur’s fortunes. Probably foremost among them was Sterkur Fálk, the thein of Vonskil; Fálk steadily built a hitherto-unthinkable coalition of Siur polities which, in 1623, became Siurskeyti; he himself became the first man to hold the title of thár in almost eight centuries as a treaty of federation, the Sáttmáli, was signed.

1650-1800: the glory years

Fálk and his successors would drastically turn the Siur’s fortunes around, driving the reconstruction of trading power and political influence that typified the so-called Gullöld, the “Golden Age” of Siurskeyti. With ironclad confidence the Siursk fought extensive naval campaigns against Odann and, to some extent, Dordanie and Quènie in the later 17th century; and they claimed firm footholds around the Serrinean coast and, to a lesser degree, in Tisceron which would last even into modern times. Siur ships, already a commonplace in the waters south of the Strait of Calcar, began to seek out new frontiers along the western Lestrian coast. The first settlement and early expansion of territory in Siursk Serania also took place in this period; and in political terms, probably the signal achievement was the ousting of Odannach rule in the Tassedar islands – home to a now partly-indigenous Siur community for centuries – and their admission as a commonhold after the Reclamation War (1746–60). At home, growing prosperity allowed for the beginnings of a distinct merchant class and at least a degree of overlap between this group and the traditional Siur nobility, the eðalkyn. These moneyed plebeians – something of a novelty in Siur society – became known as the nýmenn, literally “new men”, after a statement ascribed to a group in Hélla in 1787 that “we are the New Men; and we will not be bound by the old ways”. Culturally, the 18th century was dominated by the Endurtendrandi or “Rekindling”, a root-and-branch examination of Siur cultural practices with the aim of purging the worst foreign excrescences and bringing to the fore just what it meant to be Siur. Sarevi, whose thein Guðmundur Bani was a key player in this movement, was a significant centre.

However, over time emerged a distinct – and increasing – shift of economic weight towards the historically more prosperous commonholds in the south. Business combines – some noble in origins, some among the nýmenn, and increasingly mixed – based in the commercial centres of Ostari, Reylatur and, to a lesser extent, Lágskáli began to gain a fierce grip over the country’s resource bases in the north. Attempts to slow or halt the process through internal tariffs and other economic measures were more often paralysed or stymied in courts. The shift was aided by a movement towards shedding the last remnants of Siurskeyti’s federal structure and creating a unitary state – quite against both the letter and the spirit of Fálk’s original vision, and protested against with vigour by the interior commonholds. Despite the efforts of moderate voices like the Siblinghood of the Axe, the last decade of the 17th century saw a clear growth and increase in vitriol in what became known as the Kall af Skyldu or “call of duty” campaign – a duty which each side defined in increasingly different terms – and a steady ratcheting-up of animosities.

1800-1930: a house divided

Increasing restiveness in the interior combined with the presence of the weak and vain Ármann Lindskold as thár and the willingness of coastal commercial financiers and rentiers to manipulate him into backing their interests; the result was the secession of five inland commonholds in 1812, led by Helminthasse (which became the common name of the country by a process of osmosis). The rebels and the rump Siurskeyti fought a short and largely inconclusive war over the split; both nations' histories refer to it as the Summer War (Sumarstrið), although a more poetic and more widely-preferred name is the Skammarstrið, sometimes translated as the “War that Died of Shame”. This lasted some eight months before saner heads prevailed and the secessionists were allowed to go their own way.

While the secession and its immediate aftermath was a traumatic period for both nations, for the new Helminthasse, this was the beginning of the period of the Silfuröld or “Silver Age”; the new Helmin alliance used its substantial resource base (including colonial possessions that had sided with the rebels) to build a strong economy – a feat achieved to some extent at the expense of Siurskeyti, now obliged to treat with its new neighbours on terms more favourable to the Helmin. As the country’s relative strength improved, suspicions over continuing Siursk claims to Helmin territory began to recede, and the two countries slowly accustomed themselves to peaceful co-existence and (occasionally grudging) co-operation.

With a relatively stable peace in place on one border, Helminthasse turned its attentions to its other flanks – with mixed results. Alliances were forged with Savam, always anxious to discomfit the Siursk, and with Elland; but overconfidence saw the Helmin hammered by Odannach forces in Vettermark in 1833 as they intervened in support of local Arlaturi, with the loss of the southern Sporður region to opportunistic Alcasian attack into the bargain. The Sporður was recaptured in 1845, but Helmin alliances were fractured in the Embute War (1889-93). in which Elland fought Savam, and took years to recover.

But all was not necessarily well at home; even in the face of localised disturbances like the Trjáhestar movement in Vinhaxa and the Lanjar Rebellion in Ærlasse, there had emerged a slow, but visible, trend towards the kind of more formalised union which the Summer War had been fought to prevent. The Vinhaxan Usurpation of 1879, in which the other four commonholds used deadly force to prevent Vinhaxa from seceding, has been seen as the last spasm of true independence in the Helmin commonholds; and the “Five as One” address by Bjalla Elsturhæð in 1898 perhaps underscored this.

If this was indeed the case, though, then the shift excited relatively little comment; as the 19th century gave way to the 20th Helminthasse enjoyed a quiet prosperity and a reputation as a place well removed from the ugly disputes and rivalries which increasingly typified the Messenian continent as the decades passed one after another.

1930-present: war, famine and remembrance

The Long War catalysed changes in Helmin society, as the perceived threat from outside gave a central government leeway to accelerate that process of union as it gathered more power and control to itself. Helmin interests outside Messenia forced the country to assume a more militant posture, with the Abranoussan War of 1937-41 marking the first prolonged use of Helmin combat forces outside their home continent. Continuing tensions across the continent cast a pall over Helminthasse at various times in the 1940s and 1950s, while the country’s war in Serania against Madaria overlapped enough with the Zepnish fight against the same foe for them to make common cause in the period between 1954 and 1957. The government also took the opportunities presented by this extended period of uncertainty to draw even greater power to itself and away from the individual commonholds – creating in the process a continuing bone of contention into the present time.

However, nuclear exchange on the other side of the continent in Joriscia would produce catastrophic consequences even as far away as the Siur country, and, indeed, across the entire northern hemisphere. The Sea of Flames campaign between Terophan and Azophin ultimately brought the Long War to first a ceasefire, then a return of an uneasy peace; but the environmental damage caused climatic change on a scale not seen in more than a millennium. 1958 became known, in Helminthasse as elsewhere, as the “year without a summer” (Sumarlaust Árið) – and was the first of several, as the planet’s climate slowly recovered its equilibrium.

The agricultural heartlands of Helminthasse were devastated. A meagre harvest in the autumn of 1958 reduced much of the country to subsistence levels of nutrition, and actual famine in some regions. The country’s historically strong balance of trade from agriculture was virtually obliterated in a single year, adding financial crisis to the human-level disaster. The government under Jónas Örvum came close to buckling under the strain. As in a number of other countries in Messenia, the Helmin government introduced strict rationing – not just of foodstuffs, but of a wide range of other daily staples – while seeking to alleviate the shortages in the most badly-affected parts of the country. Örvum, hitherto dismissed as somewhat ineffectual compared to his predecessor, the wartime leader Atgervi Moll, led a tireless effort to hold back disaster; the strain of this task was probably a proximate cause of his death from heart failure in 1961.

As Helminthasse slowly began to rebuild, time prompted a re-analysis of its past position and a gradual rapprochement with Siurskeyti, as the two countries moved towards a greater acknowledgement of their common heritage and common interests in a process that has been termed opinn hendur (“open hands”) in media commentary. The rationale was summed up by Dugur Parðavar, then althein of Helminthasse, in an address to the Siurskeyti legislature in 1975, during the first visit by a Helmin head of state in almost fifty years: “Brother may dispute with brother; no family is perfect. But even the brothers who quarrel with each other will still stand together against any and all who threaten the family.” These years saw the growth of a greater sense of confidence by Helminthasse on the interordinate stage, as greater prosperity gave it a stronger will to impose itself on world affairs; the period roughly from 1970 to 2000 was one in which Helminthasse showed genuine signs of seeking to throw off its traditional second-rank status in the world community and to take a seat at the top table alongside the great powers.

The 1980s saw significant changes within the Helmin business environment, driven largely by a shift in government philosophy away from the traditions of statism which have been dominant in much of Messenia for many years. During his twelve years in office as alráðherra or chief minister (1980-92), Högni Traustur pushed hard for the divestment by government of substantial stakes in what had been state-owned enterprises, notably in electricity and gas supplies and telecommunications (the railways were a notable exception, having been taken into public ownership too recently for Traustur to successfully reverse the decision). While the decision has been decried in some parts – and while efforts have been made to wind back the sell-off by some of Traustur’s successors – the new state of what are now in many cases public-private partnerships seems now to be well-entrenched, with more recent governments lacking in sufficient will or political capital to drive such an effort.

However, in the past twenty years Helminthasse has been forced to confront the beginnings of a slow and painful transition towards a post-industrial economy as its mainstays in coal, steel and timber begin to expire. Helmin historians are beginning to speak of the modern era as the Koparöld or “Copper Age”, although many feel that Ryðöld or “Rust Age” may be more appropriate.

Government and authority

Helminthasse is an elective monarchy, with the althein being chosen from within the noble houses of the five member commonholds at five-yearly intervals; no person so elected may serve consecutive terms as althein, although there is no constitutional bar to a second non-consecutive term. This was a deliberate departure from the practice within Siurskeyti, whose thár may, in theory, hold his position indefinitely (albeit subject to other constitutional safeguards). The first Eðaldeild had been conscious that the presence of a weak thár held in office by commercial interests had contributed largely to their decision to secede from Siurskeyti. The current practice has been criticised as contributing to a short-term political outlook, although the present-day Eðaldeild, in its role as advisor to the althein, provides for a measure of continuity.

Despite the reservations of the Helmin founding fathers, the role of the althein was, at its outset, modelled substantially on that of the Siursk thár – that is, with a very large measure of executive authority, tempered by the support of (and, to an extent, scrutiny by) a council of advisers. The development of more respopular principles of government in the Siur country has weakened this position, although the althein’s responsibilities have never diminished into the purely ceremonial role of a constitutional figurehead.

The role of head of government is now filled by the chief minister or alráðherra; he may be appointed from either house, as may his cabinet, although there has been a largely unspoken convention over the years since the Long War that the chief minister be from the Fόlksdeild, given the perceived wider base of opinion represented by the lower house’s electorate. The althein and alráðherra customarily work closely together, although differences in political stances have often strained the relationship.

Helminthasse maintains a bicameral parliament, the Landsþing. The upper house, the Eðaldeild, is the functional descendant of the Samhaltráð, the noble council which advised the thár of Siurskeyti, and comprises representatives of the eðalkyn, the highest of the Helmin noble houses; it has only a negative voice and cannot vote down legislation, merely return it to the lower house for further scrutiny. The Eðaldeild has the additional constitutional responsibility of electing the althein. The membership of the Eðaldeild has fluctuated over time, but has been fixed at thirty (six from each commonhold) since 1907. The lower house or Fólksdeild is not directly elected by the people, despite the name; rather, its membership is by appointment from the five unicameral viðaldsdeildir or commonhold chambers, although membership of these bodies is a prerequisite and is by general election for a maximum term of five years. The composition of the Fόlksdeild has varied, but is currently fixed at 129, subject to periodic review (the next such being due in 2023).

“Parties”, as such, are largely alien to Siur politics; alliances are essentially factional, gathering around particular causes or, in some cases, individuals. The peculiar arrangements of the Fόlksdeild give individual commonhold blocs arguably undue strength, as passage of a bill requires a double majority, both of delegates and of commonholds.1 The practice, the creation of the former alráðherra Viska Skaft, is intended to ensure, as far as possible, that legitimate grievances within the country may be defused before a particular piece of legislation passes through the Landsþing.

In 2005, the central government under then leader Eir Dæld adopted a scheme of election by universal suffrage, with the age of majority set at 16 years in accordance with long-standing Siur custom, abandoning the traditional amskyldr system still used in Siurskeyti. The change was fiercely disputed, and its passage through both houses of the Landsþing was achieved narrowly, not least because, although officially cast as a “recommendation”, it was seen in some quarters as an imposition from the federal level, in contrast to the more traditional bottom-up nature of Helmin (and Siursk) government. The long-term effects of the change arguably remain to be seen in full.

Commonholds

Helminthasse retains, with minor adjustments, the original boundaries of the five commonholds which formed the country at the time of the split with Siurskeyti, and these form the primary political units of the current-day state.2 The five commonholds (viðaldar) are, in alphabetical order: Helminthasse, Sarevi, Vinhaxa, Ærlasse and Æthelin. Each of these is divided into smaller administrative districts called húðir, “hides” (a traditional Siur unit of land measurement), the number dependent upon size. Vinhaxa, the smallest commonhold, has fifteen húðir; Sarevi, the largest, has 37. The húðir were at one time coextant with the domains of individual eðalkyn, although shifts in population over time have substantially broken that link.

Overseas possessions

As a legacy of the secession from Siurskeyti, Helminthasse holds three overseas territories,3 Jannaland and the Múskatströnd in southern Serania Major, and Kisilland in western Lestria. All three have internal governing bodies modelled after the Fólksdeild, although responsibility for foreign policy and defence remains with the home government. Following the Dæld reforms of 2005, all citizens of adult age may vote; Kisilland additionally sets aside four seats in its chamber specifically for indigenous communities who may otherwise not be represented. As with some other Messenian states, territory citizens (tryggsmenn í útlandi) have somewhat restricted citizenship rights in Helminthasse proper.

Foreign policy

A significant part of Helminthasse’s foreign policy is governed by its relationship with Siurskeyti. While nobody seriously sees actual reunification as an option, Siursk claims to political and economic dominance over other Siur polities has still been a persistent sore point, and Helmin governments have sometimes deliberately set out their stalls in counterpoint to attitudes in Ostari.

Elsewhere in Messenia, Helminthasse has maintained formal ties of alliance with Savam for most of its existence. Through Savam’s own alliance network the Helmin have also co-operated closely with Zeppengeran, although past Helmin governments have been wary of the oligarchical nature of their counterpart in Henver since the rise of the New Alignment Society there. Relations with Odann, the other Messenian great power, have been similarly guarded in recent years. Ties to the major Joriscian powers have been limited, largely due to distance, although relations with Agamar have warmed of late as a side-effect of Sakari’s improved relations with the Savamese.

Military

Early Siur society accepted, as a given principle, the right of the thein or thosse to the service in arms of those who had sworn themselves to that purpose in times of war; and the principle still underpins Helmin military service in that, in theory, every person capable of bearing arms may be called into the armed services if required. In practice, Helminthasse maintains a relatively small standing, professional military, which is augmented by conscription; military service (herþjónusta) lasting eighteen months is mandatory for all Helmin citizens at some point between the ages of 16 and 24, and some form of weapons training at least once a year is required of all citizens below the age of 55. The state-controlled community service organisation Ein Átt, established under the Directed Citizenship reforms in 1994, has become an accepted alternative.

Helminthasse maintains an army (Landsher) and a navy (Sjóher), although the latter is smaller than might be expected from a country of its size given Helminthasse’s limited coastline. Naval functions overlap to a degree with what would be considered coast guard responsibilities in some other countries. The country has no separate air force; instead, the army and navy each include air corps (flugherdeildir) in their operational strengths.

Along with the normal extraterritorial deployments consistent with the demands of outland possessions, the Helmin armed forces are also subject to deployment as required by foreign policy and patterns of alliance. The only recent such instance was in southern Transvechia, where both Helmin and Savamese forces were assisting the local government in maintaining order in the restive Baseriote regions after the quelling of the Baseriote Insurrection (2004-07); however, the Transvechian government has ended the state of emergency in the region, and all Helmin forces returned home by the end of 2021.

Finance and economy

For much of their recorded history, the commonholds that today form Helminthasse have earned the greater part of their living from natural resources. In antiquity Helmin-mined tin was exported across Messenia for use in manufacture of bronze; in the great age of sail, Helmin timber built the ships with which Siurskeyti ruled the Medius, and the Helmin commonholds grew the flax for their sails. Helminthasse’s rise to industrial prosperity was underpinned by its reserves of coal and iron ore, producing top-quality steels.

Much of the development of the Helmin economy as it moved away from its agrarian roots was financed by the treasuries of the country’s noble houses. This was in many respects a manifestation of Arlaturi philosophies; the Siur and Helmin nobility have over centuries felt themselves largely obliged to justify their superior status in society by taking a lead in matters that would further the prosperity of their people. In the process some theinic and thossic houses turned themselves into substantial drivers of growth in their own right; indeed, the construction company Vestarkul HF, of Helmin origin (although now incorporated in Siurskeyti) was originally established by the thein of Vinhaxa in 1058, and is recognised as the oldest limited company in the world.

However, there is increasing concern that Helminthasse’s long marriage to heavy industry may be heading towards divorce. Coal reserves are in decline as pits near exhaustion, and cheaper steel production from other parts of the continent is creating problems for the steel industry. The great Helmin forests now provide wood primarily for paper making. However, some new industries hold out the promise of success in the future. With oil prices rising, the cracking of underground shales for oil is now becoming a viable proposition; and the Aphrasians have cast up significant deposits of rare earth metals – notably scandium, neodymium and dysprosium – which are becoming vital to high-technology manufactures, as well as small quantities of uranium and thorium. The mountain rivers of the region are now being bent in places to the production of hydro-electricity.

Even with all this change, some old stalwarts remain. Helmin agriculture and the dairy and livestock industries continue strongly; Helminthasse has traditionally been good country for viniculture, and Helmin wines are emerging from a period of disparagement to achieve commercial and critical respect. Commercial aquaculture is beginning to grow in importance along the country’s northern rivers.

The service and financial sectors are less well developed, given the dominance of extractive industries within the Helmin economy in the past, a position which has been addressed somewhat imperfectly in the last thirty years. Many of Helminthasse’s best known names are either joint ventures or otherwise under partial foreign ownership; current legislation forbids ownership of Helmin companies by foreign entities beyond a 30% stake - and entirely in areas which the government regards as "sensitive", itself a somewhat nebulously defined concept - although even this has caused difficulties, given the potential for blocking tactics and "negative control" that this makes possible. Concerns are strongest as regards Siurskeyti, given the lack of a language barrier; and the extent to which Siursk finance influences the Helmin economy is a continuing concern to the government.

Ethnology

Helminthasse is largely ethnically homogeneous, with only a fairly small percentage of the population identifiable as útlendingar (the term means "foreigner", but is frequently used as a catch-all for people outside the typical Siur phenotype). This is largely an accident of history, as people coming to Siurskeyti from its Median island and Ascesian possessions tended to settle in coastal regions, away from the inland commonholds which became Helminthasse. The country's one native minority group is the Enða, a traditionally itinerant people believed to have originated in south-eastern Messenia around the beginning of the Common Era; most Enða live in the mountain eastern regions, mainly in Ærlasse. The Enða language has officially-recognised status in Ærlasse, although not at national level.

The most recent census (2015) broke the population down by ethnicity thus: Siur 90.7%; Enða 2.6%; Lestrian and Median islander 1.3%; Ascesian (Sæmunsvarskur) 1.5%; other Messenian 3.9%. This may be inaccurate to an extent, given the strong tendency in both Helminthasse and Siurskeyti to identify as a "Siur" on the basis of cultural and religious matters rather than place of birth or ancestry per se.

Culture

Common origins and a long shared history have meant that Helminthasse culture overlaps strongly with that of Siurskeyti, and the sentiment of “Siurness” or sígafa is a real and pervasive influence in both countries; for many outsiders this has created an occasional sense that they are “two countries divided by a common language”. The typical Helmin is thus often irritated by the use by outsiders of the term “Siur” only for their neighbours (the correct usage is Siur for the overarching cultural group in western Messenia, and Siursk when specifically referencing matters relating to the country of Siurskeyti and its citizens). Even so, the long history of rivalry between Helminthasse and Siurskeyti has fostered an odd love-hate relationship between the two nations, as well as an extensive lexicon of insults and put-downs on both sides of the border. While Siursk jokes tend to depict the Helmin as rural bumpkins of limited intelligence, the stock Helmin perception of the Siursk tends to focus on flash and bluster, and a sense of self-importance bordering on arrogance; the distinction is sometimes a source of amusement to non-Siur who often regard Siursk and Helmin alike as remarkably drab.

Religion

The history of Helminthasse is very tightly bound up with the history of Arlatur, which has been the dominant faith in the region since the beginning of the tenth century; Ragna Hrafnamaður, also known as the Summoner, the founder of Arlatur, was born in what is now the Siurskeyti exclave of Hélla in the north-west of Helminthasse, and Helmin Arlaturi have played no less a role in the development of the faith since the Summer War than had been the case during the previous centuries. An overwhelming majority of Helmin self-identify as Arlaturi; the faith has been considered as a key element of Siur identity for over a millennium and, although modern susceptibilities may have slightly loosened its grip, the presence of the Arlatur communion is still a real and vibrant matter in contemporary Helmin society.

However, this has not precluded the presence of other faiths; the practice of other religions, while not expressly protected in Helmin law, has been a long-standing custom. The commonhold of Ærlasse is home to the vast majority of Siur Cairans, where they constitute almost 10% of the population, and the local capital, Öldhólmur, is the seat of the Argan of the Siur. Siriash is much more sparsely represented; and current attitudes to Siriash in Helminthasse have deteriorated markedly in the last century. Bhramavada, introduced by Sæmunsvarskur and other Ascesian expatriates, is present at a very low level, and is almost completely confined to Virkið and Lágskáli, as is the Pyranism brought into the country by immigrants from Kisilland.

Arlatur’s influence on Helmin government is open to interpretation; for the most part, the councils of Arlatur have not sought to exercise formal influence over the machinery of government, and most Helmin have decried the idea of a defined voice to the communion there. However, a strong informal influence is not denied, although all parties involved are insistent that it operates only at the general level at which faith informs the conduct of the individual.

Art, science and literature

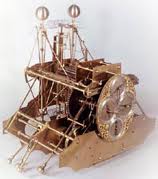

While an argument can be made for scientific progress in earlier history – evidence suggests that the neolithic Vítrör people practiced primitive dentistry, and the megalithic structures of the early Jötunsteinn are believed to have had a role to play in astronomical observations and calculations – the inquiring mindset fostered by early Arlatur helped to create a more positive environment for development of the sciences in the Siur lands, although the development of science in the region has historically lagged behind that of Joriscia since the rise to dominance of Vaestism in the eastern lands after around 1700. Among other examples, the 15th century Helmin mathematician and astronomer Rafðann Streymi was the first to provide a mathematical proof for a sun-centred model of Arden’s solar system (the idea had first been propounded in the third century BCE in what is now Madaria, but a proof, if then established, has since been lost); and the ocean voyages of Siurskeyti’s military and merchant fleets were aided greatly by the development of accurate marine clocks after the 1710 design of Kastur Tiginn, a Helmin self-taught engineer and horologist employed by the Siurskeyti naval office.

Arlaturi sensibilities on the development of one’s spiritual essence (neisti) directed attention to what are termed social sciences today. A particular strength was in the development of penology during the 17th and 18th centuries, with Járn Boginn (in prison design) and Lenna Ýviður af Svansey (in the treatment of prisoners) regarded as pioneers in their respective fields.

While the Siur country has been no stranger to traditions of epic oral culture (the 14th century Codex Scalholti transcription, attributed to Hófsóley Dánar, thein of Skálaholt, includes pieces at least seven hundred years older, and two which may even date to the earliest emergence of Hártal as a distinct language), its more recent literary tradition has been poorer by comparison. Post-secession Helminthasse has produced few authors worthy of wider critical acclaim (and its only real contribution to Messenian literary canon, Hvalurinn by Aðal Mælarborg (1851) is sometimes cited as the most boring “classic” novel ever written). However, modern genre fiction has produced more successful writers (commercially and critically) within Helminthasse, of whom the widest known at present is probably Áttundi Héllur, author of crime and espionage fiction and creator of the diplomat and spy Parrandar Lind.

Notes

- ↑ It has not been unknown for a bill that has a majority of support to fall because its support is too heavily concentrated in particular regions.

- ↑ Somewhat confusingly, the original commonhold of Helminthasse retains its old name; a 1987 plan to rename it as Helminlandir, “Helmin lands”, was voted down, with 88.4% of those polled rejecting the proposal.

- ↑ The term “colony” is officially deprecated in Helmin government statements.