Savam

Savamese Empire Empire savamais Other languages:

| |

|---|---|

| Motto: Édif, l’Empereur, le peuple, unis pour toujours “Aedif, the Emperor, the People, united for ever” | |

Anthem: Chant de l’union “Union’s Song” | |

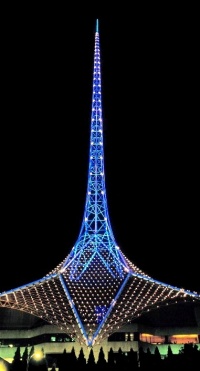

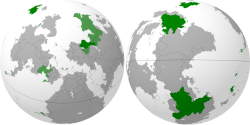

The Savamese Empire (dark green, including overseas possessions) and its protectorates and client states (light green) | |

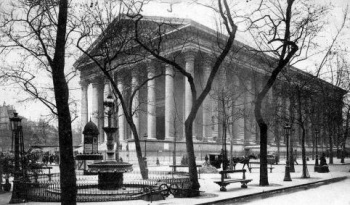

| Capital and largest city | Quesailles |

| Official languages | Savamese |

| Recognised regional languages | Verborian, Embute, Samezeau, Squade |

| Religion | Cairony |

• Argan | Reformed Savamese |

| Demonym | Savamese |

| Government | Federal parliamentary and respopular respublic, and elective constitutional monarchy |

• Emperor | Valentin III |

• Viceroy | Camille de Lautrec |

| Legislature | Parliament of Savam |

| Formation | |

• Unification | 1798 |

| Area | |

| 706,956 km2 (272,957 sq mi) (19th) | |

• Doreysne | 10,487 km2 (4,049 sq mi) |

• Totala | 13,964,994 km2 (5,391,914 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 168,255,503b |

• Density | 238/km2 (616.4/sq mi) |

| Currency | Aurel (₳) |

| Time zone | Quesailles Time IAT - M reference |

| |

Savam, officially the Savamese Empire, is a country located in north-eastern Messenia, with overseas territories and colonies extent in the Medius Sea and the Seranias. Savam is bordered from west to east by Brolangouan, Emilia, Brex-Sarre, Cantaire, Ceresora, the Rastovid Confederacy and Transvechia. It is bounded in the north by the Arcedian Sea, while its southern border roughly follows a straight line from Lake Carles to the Great Lakes via the Twin Lakes. Most of its territory lies in the alluvial plains of the Gaste and Védomagne rivers, that both empty into the Fulvian Gulf in the country’s east. It is the second largest country in Messenia, after Ceresora (if excluding the Transvechian north).

One of the world's Great Powers, Savam is a federal constitutional respublican monarchy with significant respopular elements. Governmental powers have shifted from the aristocracy and Cairan clergy to elected or technocratic magistrates, although the nobility continues to enjoy a number of privileges. The Savamese Empire was founded amidst the Reform Wars as a result of catholic debates and the Imperial Question, forming a united front of the Sabamic Cairans adhering to the Cairan Reformation. Although the catholic goal, unifying all Cairans, remains, it has today became an undertone and has been replaced by a policy of integration of all ethno-cultural groups believed to belong to the greater Savamese people.

Savam’s population is just over 168 million, the largest in Messenia and second only to the Lutoborsk in the civilised world (accounting for metropoles only). Its citizens enjoy a high standard of living allowed by a developed mixed economy, of which many aspects are controlled directly or indirectly by the government. The private sector represents about 60-70% of the national product in the early 2010s, and is spearheaded by major Aristocratic polyindustrials. The government retains direct control of strategic assets and almost all utilities, and closely regulate and intervene in the financial sector. Savam is rapidly closing on Joriscian nations in terms of technological development.

Physical geography

Savam proper is located between latitudes 43° and 53° north and near the eastern edge of Messenia. The state of Benovia does extend as far as western Translacunia. It is the second largest country in Messenia, after Ceresora (or third if counting all of Transvechia as Messenian), with a land area of 706,956 km² (the 19th in the World).

It is bordered in the north by the Arcedian Sea, with the Fulvian Gulf and Occes Bay respectively east and west of the Quenian Peninsula. Most of Savam's western coasts are indented rocky small bays and peninsulas, with high cliffs quite common; the long straight line of the Falaises de l'Odet is certainly the most famous such cliffs system. Eastern coasts in Lower Gaste and Lower Védomagne are flatter with sandy beaches and, historically, swamps; the Sablons, squeezed between the two great rivers, is one of the largest sand accumulation in Messenia.

Savamese often refer to the “southern coast(s)” while speaking of the multiple lakes dotting Savam’s southern boundary. Savam is the only country that has coastlines on the three large lake systems of Messenia. It owns the northern coast of Lake Carles as well as a portion of the north-eastern coast of Lake Gorya, one of the Great Lakes; the Twin Lakes are almost completely included in Savam’s territory. Savam has extensive river systems. The two principle rivers are the Gaste and the Védomagne, which both empties in the Fulvian Gulf and form the alluvial plains of Dordanie, the country’s core. The Védomagne Delta is a fertile region of great biodiversity. Another important river is the Génestre, which fuse with the Védomagne at the city of Porians after crossing the Twin Lakes.

The country can be broadly divided between two types of landscapes: alluvial and coastal plains, and hills and low-lying mountains. More than half of the country lies in the greater alluvial plains of the Gaste and Védomagne, known as the Sabamic Plain. The Sabamic Plain was naturally covered in woodlands and marshes, but millennia of human exploitation has converted it to farmlands; most marshes have disappeared and woodlands mostly remain in the low-lying hills that crisscross the plain. The other significant plain is the Quenian Plain, which is separated from the rest of Savam by the Massif Cardussien.

The Massif Cardussien is formed by a string of hills that reach about 950 metres above sea level (highest point at the Quicheri de Bollère, 959 metres), in a larger inverted-L shape pointing to the north and west. Lower ridges extent to the south in Adaque and the Cardussian Piedmont. The hills in southern Adaque are not part of the Massif, as they are a northern extension of the hills of Estologne. Moving further west, the Massif Cardussien is separated from the Rindarian Range by the Sillon de Velcour. Most of the Savamese Rindarian Range is composed of hills not different from the Massif Cardussien. Nonetheless, in the country’s extreme west, the Rindarian Range reaches altitudes between 1,000 and 1,300 metres. In the east, Benovia is Savam’s most bumpy region, with most of the state’s above 500 metres. The area forms the piedmont and south-western extremity, the Benovian Range, of the Severnistines that stretch to the Arctic. About a third of the state lies above 800 metres, with the highest point, also Savam’s, at Mount Belgoni (1,617 metres). The region is characterised by several large valleys that concentrate human inhabitation.

The Védomagne river bisects the very end of the Severnistines by passing through the Janneur Valley, a recent tectonic graben enlarged by subsequent glacial erosion. Immediately to the west is the only flat land route between Cislacunia and the Sabamic Plain, the Sabamic Gate.

Climate

Savam is located within the temperate zone and its climate is overall transitional between the Arcedian and the continental climates. The country marks the eastern-most influence of the Riach current which warms the northern Messenian coast compared to other areas of similar latitude. Savam's coasts remain ice-free throughout the winter, except during exceptionally cold ones (such as the artifically-induced Years Without Summers)

Most of the country falls into the Arcedian zone, with high level of rainfall, mild winters and cool to warm summers. Ysan has this climate, with average daily temperatures of 14° in Dominy and 3° in Petrial. In the south-east (Occois-Garde) and deep east (Benovia) the climate is continental with warm, stormy summers, colder winters and some less rain; the Cardussien and Rindarian mountains also experience a similar continental climate, though with higher rainfalls than in the lowlands. Ostelac is an example of this climate, with average daily temperatures of 21° in Dominy and -2° in Petrial. In higher altitude areas of the western Severnistines the climate follows typical patterns evolving from continental in the valleys to high-altitude over the tree line via an intermediate boreal zone.

Precipitations are spread about equally during the year, contrary to the typical patttern in the Arcedian climate area in northern Messenia where precipitations tend to be higher in winter. Precipitations patterns are governed by the interactions between fronts at the interface between the zones of influence of the perennial Diothún High and, depending on the season, the Inner Joriscian High or the Borean High, allowing eastward-moving fronts to penetrate to varied depths within Messenia from the Arcedian Sea. Savam differs from the overall pattern to its west due to being located closer to the centre of the Inner Joriscian High, which grows particularly strong in winter but dissipate in summer. Lake-effect snow is a significant phenomenon in the south during the winter, around the Twin Lakes and in Valdenois and neighbouring Emilia.

History

Government and authority

Government

The Savamese Empire is a federal respublican monarchy with a number of respopular principles and institutions, a form of enlightened respublic; its six members states are constitutional monarchies, while the federal government is divided between an elected sovereign and a representative respublican structure. The current constitution of Savam was adopted in 1919, introducing several modifications to the original 1798 text and has been amended on numerous occasions ever since. Cairony is the state religion, nonetheless a limited degree of religious freedom is protected by law.

Since its formation in 1798 as a mostly confederal system, Savam’s federal government has been gaining more power over the member states, especially after the Embute War, tending toward an increasingly centralised federal situation. The domination of Dordanie over other states, which has been the source of recurrent troubles, is essential in this centralisation tendency. Quesailles, shared capital of Dordanie and the empire, has been attracting economic and political power. However, another major factor that drove centralisation is the influence of Radicalism, which has left a strong mark on current Savamese institutions and political mores following the Labarrist Age.

Sovereign

Savam’s head of state if the Emperor of the Savamese (Empereur des Savamais), whose role is largely ceremonial. The Emperor is the supreme representative of the Savamese people and a sacred figure in Cairony, co-head of the Argan of Savam although actual religious power is into the hands of the Holy Mother of Savam (Sainte-mère de Savam). The Holy Mother’s status is very high in Savam; she is the only person not required to address the Emperor with the official style Your Imperial and Royal Majesty. The Emperor is elected by peers for a life-term among the realm sovereigns. The sovereign of Dordanie has been elected to imperial dignity all but four times since 1798, and continuously since 1889, which has formed a quasi imperial dynasty in Quesailles.

Due to the making of the constitution, the head of state has little effective authority on the government's everyday proceedings at a federal level (He or She retain their power at state level). Nonetheless, many ways to influence the federal government remain. Primarily, the Emperor can veto law enacted by the parliament; this veto can only be annulled by a conjoined vote by all three chambers (in Savamese respublican government, monarch assent is not necessary for law passed by the legislation to be enacted). The Emperor can also dissolve the Assembly of Commons, but only on the request of its speaker, or alternatively refuse this request. Another way for the Emperor to influence the government is by delaying the opening of new sessions at the Commons; the Assembly cannot start a session without the opening ceremony being attended by the Emperor or one of its appointed representative (called a Ministre lieutenant).

Finally, four of the 14 members of the Council of the Chancellorship are appointed by the monarchs of the four original member states, one of whom is always the Emperor; the Emperor, and fellow monarchs, can influence government policy quite effectively by appointing a confident to the Council.

Executive branch

The Viceroy (Vice-roi) is Savam’s head of government, the actual recipient of executive power. The Viceroy is a politician elected directly by voters for a 5-year term. The Viceroy chairs the Council of the Chancellorship (Conseil de la chancellerie), a body of fourteen Chancellors (Chancelier), and leads governmental action.

Although it is not necessary for the Viceroy to have parliamentary support, it is generally the preferred state of affairs; indeed, the Viceroy must enact the laws passed by the parliament and has no veto capacity. Parliamentary confidence in the Viceroy is thus preferred to smooth the proceed of governmental affairs; to make this more likely, the viceregal and parliamentary elections are held together (every second cycle for the Assembly of Nobles). If a Viceroy were to leave office before the end of their terms tradition dictates that the Commmons dissolve themselves to enable a new legislative election at the same time as the upcoming viceregal one. However, this tradition is not set in the constitution and has not always been applied.

Chancellors hold ministerial-like power individually as well as collectively. Contrary to many other countries, there are no de jure specialised ministerial positions in Savam (the ministry-like institutions exist, usually called a directorate (direction) or a magistracy (magistrature) in Savamese -- the only institution that is named ministry (ministère) is the Foreign Ministry, due to historical reasons). The Council of the Chancellorship can take control of any matter it deems necessary but remains assisted by high-level civil servants (hauts fonctionnaires) for the daily management of federal directorates, the equivalent of ministries in other countries.

All the Chancellors are not appointed in the same way. There are six “civil” chancellors, which are selected from the civil society, business and corps of the administration: intellectuals, former politicians, business-people, former high-level civil servants, etc. They are appointed by other chancellors via a peer-selection process, in complete independence. Four more chancellors consist of two “aristocratic” chancellors elected by the Assembly of Nobles (Assemblée nobiliaire), one chancellor appointed by the Argan of Savam, and one chancellor appointed by the Joint Staff; the latter two chancellors being serving members of their respective organisations. Finally, the remaining four chancellors are the so-called royal chancellors because they are appointed, one each, by the sovereigns of the four original member states (Brocquie, Dordanie, Quènie, and Valdenois).

Officially the Council and the Viceroy exercise their power under the authority of the Emperor; in practice, however, the Emperor is mostly withdrawn from government dealings (due notably to compromises made in 1798 during the drafting of the Constitution). In case of national emergency, the clause discrétionnaire of the Constitution allows the Viceroy to receive temporary absolute power; the clause also allows such authority to revert to the Emperor in the case the Viceroy was unable to exercise the pouvoirs discrétionnaires.

Legislative branch

The Savamese parliament is a tricameral legislture comprising the Assembly of Commons (Assemblées des communes), the Assembly of Nobles (Assemblée nobiliaire) and the High Assembly (Haute assemblée). Parliamentarians at the Assembly of Commons represent local constituencies and are directly elected for 5-year terms. The Assembly of Nobles is divided between members which are elected by, and among, the whole noble population for 10-years term, and members with life-long seats based on their titles, whose rosters the assembly can modify at will. The High Assembly members are chosen by an electoral college made of all elected officials in the country for 10-years terms. The three chambers act in coordination to vote laws that they can propose, or that have been proposed by the executive branch.

Separation of powers

There is a rather strict separation of powers between the executive and legislative branch at the federal level, although a number of connections between the two branches exist; the judiciary is completely separate from the two other branches. The structure of the Savamese federal government can actually be argued to go against the trends in the evolution of the respublican system over the past centuries. Indeed, while the Emperor does not exercises any authority, the executive branch is lead by a powerful directly-elected Viceroy and the technocratic Council of the Chancellorship, neither of whom are responsible to the legislative branch or, conversely, can affect legislative procedures or refuse to apply (veto) passed laws. Bridges in the separation of power are found in the Emperor’s ability to veto legislation and dissolve the Assembly of Commons or parliamentary appointment of some magisterial positions.

Note that the situation in states does not necessarily reflect that of the federal level. In many states a degree of fusion of powers at the benefits of the legislative branch exists, typically with the parliamentary speaker, the chancellor, being the effective head of government. The states of Brocquie and Valdenois are the only exceptions, maintaining stricter separation between a monarch-led executive and the parliament, although the parliament retains the authority to check monarch’s actions such as appointments, typical of the classical Sabamic respublican system.

Politics

Savam has a long political tradition, that can be traced back to the res publica of the ancient Sabāmanians and slowly opened to more part of the population from the 18th century. For most of its history, the respublic was a system that incorporated only the noble population. Before the franchise was broadened, at most 15% of the adult population was eligible. As a result of political conflicts and the influence of respopular philosophy, the franchise was slowly broadened during the 19th century until the adoption of the quartiles franchise system in 1903.

The quartile franchise divides citizens in four quartiles according to their taxable income, with the three top quartiles being allowed to vote via a weighted system; the higher the quartile one citizen seats in, the larger the weight applied. As a result, the electoral system in Savam is decisively favouring the upper classes. Nowadays, about 60% of the adult population (over 25), men and women, can vote. Nobles can always vote, even if for some reason they found themselves in the bottom quartile.

As a result the role of nobility in politics has somewhat diminished, with the Assembly of Nobles and the two noble Chancellors remaining as their sole specific institutions. However, since the majority of nobles are part of the upper-middle and upper classes, most politicians are from noble extraction as well as most upper-level magistrates. The aristocracy, the so-called Lord Farmers, retains a considerable sway via its economic power, stemming from land and business ownership. Many Viceroys have been of noble extraction, and aristocrats often sponsor political factions to directly weight on the country’s affairs.

Politics in Savam function along two levels: the state (local) and federal levels. Each state has its own political life and its own political movements, tendencies and influences that differentiates it form the other states. However, the ongoing slow shift of Dordanic-centric centralisation is making the distinction between local and federal politics less relevant than in the past.

Ideologies and factions

There are a number of ideologies competing for power in Savam, expressed by various groups of interests. The most significant ideological debate is that of liberalism versus radicalism, which has been ongoing since the 19th century. In concrete political terms modern liberals support confederalism and state's rights, parliamentary primacy, limited suffrage, a conservative moral order, laissez-faire corporate capitalistic economics and protectionism. On the other hand radicals advocate a centralised government with a strong executive (federacy), a broadened electorate, progressive social policies, and mixed economics with state-led dirigisme (essentially a form of state capitalism) and free trade. This debate is mirrored into the tug of war between the generally laissez-faire-minded political establishment and the interventionist managerial functionary class in the federal government. Moderates represent a significant third force that seeks compromise between liberalism and radicalism under the theory of Conciliatorism.

Factions

Politicians typically form associations, rallies, clubs or think tanks, usually called factions, where they can gather around some shared interests and values. While the formation of these groups is mostly ideological, it is by no means necessary. At all times, rallies have formed around charismatic individuals, the prime example of this being Marshall d'Hoste-Labarre, or around wealthy patrons, providing some prime examples of clientelism. These factions are usually only used to debate politics and coordinate some action between their members, for example in parliamentary debates and committees; members are still entirely responsible for managing their election. There is no consistent ideological bounds on all issues, nor any obligation to do so; members of one group are often found voting differently than the majority of their group on varied issues. However, for issues deemed as vital by the faction, however, a preliminary concertation is often organised so that all the faction’s member can vote en masse on these issues.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the major factions and groups are:

- the Radical faction

- the Liberal faction

- the Moderates - a fluctuating group that has a small consistent core but often overlaps with both liberal and radical factions as per its core ideological tenet of conciliatorism

- the Values’ League - a group defending conservative and traditional social policies

- the Clerical association - a faction regrouping elected officials that are also clergy members

- the New Orangists - a group supporting major socio-political reforms motivated by prioritarist utilitarianism

- the Verborian Block - a faction regrouping elected officials that wish to defend the interests of the Verborian culture, particularly well represented in Benovia and eastern Dordanie; mostly works as a big tent group, though it generally leans toward liberal or moderate positions.

Historical overview

The broader ideological axes and debates that animate Savamese political life all stem from the 18th Century's emergence of a political philosophy of the Reformation. Philosophers like Pierre Disault argued that the entrenched respublic, restricted to the nobility, was inefficient and monopolistic, betrayed its own ideals of "public matters" and meritocracy, and proposed that Egalitarian principles from the Reformation should also be applied to the economic and political system. Disault envisioned the concept of positive liberty and natural rights, seeking a government that "respected the freedoms of the governed". He argued against the very concept of nobility and focused instead on the "productive classes". Mirroring similar developments in the religious sphere, individualism became an important topic of discussion among the educated class; freedom of expression also was an important theme in the middle of the crisis of the Reform Wars.

Disault's ideas and the associated debates eventually crystallised into the new ideology of Liberalism, which opposed the aristocratic oligarchy of the classical respublic. Liberalism took off in the second half of the 18th Century due to its support among the bourgeoisie and the lower gentry. Indeed, two important pillars of the natural rights defended by liberalism were the freedom to seek one's economic self-interest (which was linked to the emerging concept of capitalism) and political representation. The urban bourgeoisie and lower gentry had became the so-called "productive class" which were at the basis of the economic growth in the pre-industrialising realms; although the system was already evolving it was mostly still controlled by the land-owning aristocracy and trade guilds, often mostly composed of lower nobles. The lower gentry wanted more balance against the economic interest of the aristocracy, as well as a better sharing of power in the parliamentary system. The bourgeoisie principally opposed guild monopolies, favoured the concept of laissez-faire, and wanted any representation and political influence, since the franchise did not extend to them (with the notable exception of the jurisdiction of the parliament of Quesailles in Dordanie). Over the century the economic power of the bourgeoisie increased steadily while their political power remained repressed, reinforcing the imbalance.

In the last decades of the 18th Century liberalism had gained enough traction that it eventuated in the enlightened respublic once it was co-opted by reform-minded members of the upper nobility motivated by proto-utilitarianism philosophical considerations and, more prosaically, the goal of preventing a brewing large-scale social uprising. Liberalism was thus at the centre of the imperial unification of Savam and would play an instrumental part in setting the conditions that would lead to rapid industrialisation in the second half of the 19th Century.

As Liberalism became the dominant ideology and Savam underwent industrial transformation in the mid-19th Century, new political schools emerged, chiefly lifted by a resentment against the growing social inequalities that industrialisation created. Most also argued that while the enlightened respublic was founded upon the ideals of respopulus it actually never achieved it and remained a form of oligarchy, albeit a broadened one. This broader reformist and counterculture movement was both secular and religious, expressing itself in a multitude of ideologies and movements like Utilitarianism, Radicalism, Libertarianism, Latourism, Darnelism, XXX, and movements associated with organised labour and Syndicalism, such as Collectivism, which rejected capitalism. A number of those movements were also pacifists in nature, opposed to Savam's war-mongering expansionism in the middle-to-late 19th Century. They thrived in the years that followed the traumatising imperial defeat in the Embute War, but not all survived into the 20th Century; indeed, the anti-establishment position of these groups made them controversial in mainstream politics and several of them were actively persecuted. The most resilient groups like the Darnelite Argan finally gained official recognition in the 1920s, though they remained on the fringes.

As years passed, the appeal of reformist politics broadened from the working class to middle-class bourgeois and lower nobles, who once again felt left behind by a monopolistic economic system that profited the aristocracy. Labarrism was the first instance of this anger taking over at a national level through the populist appeal of Valentin d'Hoste-Labarre, who is largely credited as the initiator of mass politics in the Savamese sphere. Following d'Hoste-Labarre's reign Radicalism became an entrenched mainstream ideology with mass appeal even in parts of the upper classes, which believed that the pauperisation created by industrialisation could only be alleviated by a strong, welfare-oriented, and interventionist state that supported collective labour action (within a capitalistic society). Religious arguments around the negative effects of pauperisation on the collective Cairon also played a significant role in this broadening.

In the early 20th Century, the Liberals countered the principally urban support for Radicalism by becoming more socially conservative, thus appealing to rural working classes (who may previously have been tempted by Latourism) and crystallising regionalist sentiments, opposing the centralisation-heavy Radicalism. Both sides had to deal with the continued development of extremist forms of reformism, such as Collectivism (see the Felician insurgency in Serania), which supported major upheaval of the Savamese social order into classless utilitarian meritocratic syndicalism, seen by Collectivists as the ultimate and most truthful expression of Egalitarianism.

A new period of turmoil emerged in the second half of the Long War and its aftermath. The bleak years of the troubles associated with the Ceresoran Civil War, the Gaste War, and the Climatic Correction led to a renewed flourishing of social and political movements and a thirst for change among the younger generations. In most of Messenia, similar troubles eventually led to conservative reactions, but Savam broke this trend. Radicalism became dominant again the late 1960s and 1970s and political movements like [un courant de pensée radical], the philosophical development of utilitarian prioritarianism, and an invigorated Darnelite Argan spearheaded the last wave of major societal liberalisations, gender roles changes, and statist centralisation and economic intervention. The current Savamese political climate is the continuation of the alternance between Liberal and Radical periods of government, only disturbed by the slow growth of Conciliatorism since the 1930s (the ideology of the Moderates) or the more recent emergence of New Orangism.

Media

The media in Savam is particularly invested into politics. The written press has a wide circulation (resisting the pressure of new media) and often takes strong political positions on a variety of issues. Although most news outlet will claim editorial independence in effect their ownership matters significantly over the position they take. Many of the largest circulation national papers are owned by noble corporate interests and thus generally defend liberal positions; a few notable exceptions can be found like La Dépêche cathédrale, the clergy's official publication, widely read in educated circles, or Le Courrier Public. On the other hand at a state level there are a large numbers of papers owned by trade unions and other collective bodies that generally espouse radicalist positions. A few successful independent politicians have built their success on media ownership.

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is protected by law in Savam, and helps fuel political life. However, it is not unlimited. To fully exercise their political rights, citizens have to commit time to the state in the form of the national service (i.e. conscription), both for some months in their youth and every year afterwards. Free speech is part of the rights associated with this process, and someone that is stripped from their political rights will loose it.

Ideologies and discussions perceived as undermining national unity and national security are actively censored in the media and on modern electronic networks; proponents of radical ideologies are liable to prosecution by the authorities, facing the loss of their civic rights. Even non-ideological discussion on classified government information can incur censorship.

Law

Savam uses a Mixed-Cairan legal system, where law arises primarily from written statutes; judges are not to make law, but merely to interpret it. Savamese law has two sources: Cairan law and temporal law; both are extensively codified. There is no jury system in Savam, judges are solely responsible for conducting trials. Parties are assisted by lawyers, and an Investigation Officer (prosecutor, a member of the judiciary) is responsible for collecting evidences before the trial; oral and written testimonies, forensic and circumstantial evidences are all accepted. Judges have the duty to determine whether the case depends from Cairan or temporal law, or both, as it will influence the trial’s exact proceedings. For example, Non-Cairans’ testimony might no be allowed in trials pertaining to Cairan law only.

In Cairan law, laws that govern human affairs are perceived as just one facet of a universal set of laws governing nature itself, which were set by Aedif when it designed the world. As such, violations of Cairan law are offenses against Aedif and nature, including one’s own human nature; crime is sin. Historically, the Cairan clergy has been in charge of justice, but the increasing opposition between temporal and spiritual power has led to a mixed situation. Savamese judges are not member of the clergy, although the clergy is involved in their formation and they must receive an official approbation before being able to exercise. Prosecutors can be members of the clergy, and the Argan actually holds prosecutorial powers and can initiate cases again defendants independently of the rest of the judicial apparatus. Cairan law punishments form a part of Cairon Channeling and Cairon Engineering.

Temporal law is the result of law-making activities by non-clergy rulers, typically in modern Savam the legislative branch of the government. The relationship between temporal and cairan law has been a matter of contention for centuries. In modern Savam it is generally agreed that both are of equal standing, although temporal law applies to non-Cairans too. As such, dispositions of Cairan law have been transposed to temporal law so they can apply to all individual present in the country. Many of the laws required by industrialisation and the changes brought upon society by it have been expressed in temporal terms only.

Savam’s judiciary is an independent government agency organised along a pyramidal structure with local, state and federal jurisdictions (the application of sentences, e.g. managing prisons, is a duty of the executive branch). Appeals courts exist in all jurisdiction, and the Supreme Federal Court of Savam has ultimate jurisdiction but for some specific religious subjects, where the Holy Mother of the Savamese Argan is the ultimate appeal authority. The Supreme Court is composed of both civil judges and clerical justices, and its authority is recognised by the Savamese Argan. However, only the latter can change Cairan law, according to its own internal procedures (generally a matter for the sorority). Note that judges positions are open only to the nobility.

Administrative divisions

Savam comprises six states. Formerly independent states, they retain their royal families and state constitution or fundamental laws, and enjoy a certain level of autonomy from the federal government. A legacy of Savam’s original mostly confederal government, there are some areas where states have exclusive authority; however, today the federal government has assumed full or shared responsibility in most domains. In some case, a formerly state-exclusive domain may have been taken over by the federal government but devolved to the states again. Although the states’ enactment of policy in that domain may appear identical to what it was before, with this system the federal government retains the right to end the states governance in that domain at any moment. Exclusive or fully devolved domains include local law enforcement, cultural policies, primary and secondary education, nature conservation, some local public finances and local transports responsibilities. All other government fields are either shared with the federal government (e.g. social security and welfare, healthcare, or town and country planning) or exclusive of the latter (e.g. justice, defence, tertiary education, or energy).

States are further divided into prefectures, and the largest ones (Dordanie and Quènie) also have régions regrouping several prefectures. Eventually, the lower administrative divisions to possess an elected governing body are cities (communes), which are divided between urban and rural cities (although this division is merely cosmetic). Cities are required by law to have at least 5,000 citizens of voting age (regardless of their quartile); in rural areas many small villages have fused administratively to reach the threshold. Specific administrative divisions also exist, notably regarding the judiciary. This structure is common to all states and was established during a process of administrative rationalisation in the 1930s; prior to that all states had their own diverging structures.

|

States’ governments differ between each states, despite uniformising pressure coming from the federal government. For example, most states do not have a non-noble high chamber in their parliaments, while Dordanie has one. Brocquie and Valdenois are both executive monarchies, where the sovereign is also head of government, while the other states are full parliamentary monarchies.

Benovia and Occois-Garde were until 1971 part of the Kingdom of Dordanie. The two principalities are the Savamese states with the highest proportion of non-Savamese native speakers and the only to have another language than Savamese co-official state-wide. They had enjoyed a degree of autonomy within Dordanie previously, and were granted independence during constitutional revisions in an effort to protect their cultural specificity and defuse some tensions that had arisen from the religio-cultural civil war in neighbouring Ceresora. Contrary to other states, they are not kingdoms but principalities; their sovereigns are both members of junior branches of the Flessandres-Parloy family, the ruling dynasty in Dordanie. Constitutional provisions exist to allow the re-annexation of Benovia and Occois-Garde to Dordanie, although outside of national emergency or open rebellion situations it would require the approval of their population via a referendum.

Foreign policy

The Open Seas Conundrum

Savam is one of the World’s Great Powers and thus has interests to defend all over the planet. For centuries the Sabamo-Savamese space has derived its power from its great demographic strength and the resulting economic output, which also made it one of the great sink and spring of world trade. This generally resulted in outward-focused expansionist energy, and eventually the construction of an empire in Messeno-Joriscia, Ascesia, and the Seranias.

However, unlike the other Messenian Great Powers (and their predecessors), Savam is suffering from a geographic position that gives it a harder time to access global sea power. The Savamese Navy, among the largest in the World, own backyard is the Arcedian Sea, isolated from the rest of the global ocean by the icy waters of the Arctic Sea, narrow choke-points through the often ice-locked Onnech Sound, with its sole opening the relatively narrow (in oceanic terms) passage to the Medius Sea. While not a geographic choke-point per se, the Medius Sea is, with the neighbouring Messenic Sea, the historical backbone of geopolitical and economic affairs in the Civilised World. As such, the Medius presents a militaro-political choke-point to Savam, where its ships have to cross the direct spheres of influence of competing Messenian Great or Secondary powers like Odann, Zeppengeran, Siurskeyti, Madaria, or Tassedar in order to trade or project influence further out.

Thus, ensuring free access to the seas has been a prime focus of Savamese (and predecessor states’) diplomacy for the past four centuries, especially as Savamese commercial influence in Ascesia and colonies in the Seranias grew, respectively, in the 17-18th and 19th centuries. Savam has largely counted on counter-balancing alliances and military build-up to pursue this policy. After a long struggle it somewhat succeeded in the 20th century to replace Odann as the leading maritime power in Northern Messenia, but the revival of the Pact of Clachán in 1996 has exemplified Odann's resurgence in this matter (although the Millennium Protocol has brought somewhat of a détente in the early 21st century.). Since Savamese traders have forayed in the Medius to reach Eastern Ascesia the Savamese and Siurs have often been at odds, especially given Siurskeyti's status as the domineering naval power in the Medius. To counter those interests Savam has built up a long standing entente since the mid 19th century with Zeppengeran (Savamo-Zepnish Alliance) and Helminthasse (Accord of Poignes).

Since the advent of modern ice-breakers and nuclear submarines, Savam has been very active in the Arctic Sea as a strategic glacis to which it has a strong level of control over. It is widely believed that Anthropogenic global warming will open new opportunities for Savam in the future in the Far North and, perhaps, solve the centuries-old conundrum.

Sabamic imperalism

Closer to home, a major point of focus for imperial foreign policy derives from Savamese nationalism and a notion of cultural precedence over the rest of the Sabamic and Cairan areas. The Empire considers itself the "natural leader" of both worlds, as the heir of the Sabāmani Civilisation and its Imperium and the modern derivative of the doctrine of Catholicism. While the Catholic project of yore has "failed" in the Cairan schism and the establishment of a secular empire in the reformer sphere, religion having became less and less relevant in policy terms since the late 18th century, the idea of imperial unification over the Sabamic people has a lasting influence on Savamese policy.

The upheaval of the Reform Wars saw the emergence of an orthodoxist axis between Ceresora and Odann that combined new opposition on religious lines with old political and economic conflicts. Opposing this alliance, and breaking it up, was the central fulcrum of Savamese policy up to the Long War. This eventually succeeded thanks to the fortuitous collapse of Ceresora during its bloody civil war and the defeat of an isolated Odann during the Gaste War, both in the mid twentieth century during the troubles of the Long War. While relations with Ceresora have been normalised in the post-war era, Odann's comeback on the world's stage since the 1980s has caused increased concern for Savam's interests in Messenia and worldwide.

During the 19th century within the Sabamic sphere, outside of its conflict with Ceresora, Savam followed a line of cultural expansionism and sought to unify all the people that were perceived as Savamese by Quesailles intellectual elites, including the Embutes, Transvechians, Verborians, Samezeans, Bouescians, and (to a lesser extent) the Squades. Careful diplomacy allowed to have this policy supported by the country’s southern and western allies. Nonetheless, this goal was reached with only moderate success (considering the major failure of the Embute War) and was instrumental in installing the climate of distrust and opposition that existed in the early 20th century in Messenia before the beginning of the Long War, which most visible expression was the Savamo-Odannach Cold War.

After a pause during the Long War period, where focus was monopolised by the dismantlement of the Ceresoran-Odannach alliance, this expansionist policy returned, albeit in a toned fashion. Indeed, since the 1960s, Savam has moderated its actions and rhetoric and focused on defending its economic and strategical interests in central and eastern Messenia by establishing a network of client or buffer states (including the Savamese Customs Union), expanding the so-called politics of "assimilationism" and forcing rapprochement with the empire via non-military means. Transvechia is a prime example of the kind of close client relationships Savam has established with several culturally-linked states in its sphere of influence. This approach ressembles that taken during the early 20th century, but differs markedly that a lot of focus is given on pushing economic and social interconnections and integration in order to derive political integration from them; the reverse paradigm was generally true in the earlier period.

However, the 2010s have seen a somewhat covert resurgence of more traditional and overt irredentism which has expressed itself through the passing of special citizenship legislation, homage debates in several countries, the support of re-unification movements in Brex-Sarre, and pressure to further integrate the Savamese Customs Union.

The Orient

The Savamese empire has typically tried to entertain cordial relations with most of the Outer Joriscian powers, with the overall exception of Azophin, although the struggle over Inner Joriscian and Seranian resources have not always allowed to do so. Since the twentieth century Lutoborsk and Kiy have generally been hostile to Savam's interests in Inner Joriscia and the Great North, while conflict with Azophin in Felicia is a recurring trope of Savamese foreign policy.

On the other hand, the Empire has been building a closer relationship with Agamar ever since the 19th century, as the two powers have found that their interests align fairly well, especially in terms of their mutual enimity with Azophin. Although it had started earlier informally, the Agamari-Savamese alliance was formalised for the first time in 1889 by the Treaty of Ūsilinna, the first main bilateral diplomatic treaty between a Messenian and Outer Joriscian Great Power. Since then, the two powers have collaborated on and off when necessary and in the post-Long War period actually started to increase their economic cooperation as well. In the 1990s Agamar entered a privileged trading partner agreement with the Savamese Customs Union and in the early 2000s a contract was signed between Ladaki, Agamar's national airline, and Heriault for the export of 45 Heriault TR-50 regional and VIP trijets, a rare instance of Messenian technology acquisition by an Outer Joriscian power.

In Inner Joriscia the Savamese government considers the northern watersheds of Védomagne tributaries and the Great North region as its natural sphere of influence, where it was, or is, competed by Ceresora, Kyi, Lutoborsk, and more distantly Azophin too. Several autonomous provinces within the Rastovid Confederacy are controlled by Savamese economic and political interest, including some with significant Sabamic settlements and actual on-the-ground military presence from the Imperial Army (including as part of the longstanding Operation Fluvius to protect river-bound trade from Secotic insurgents), and Savam also acts through its Transvechian proxy to project influence. Important natural gas fields are located in the Savamese sphere of influence in the Confederacy, making of prime strategic importance. The Rastovids also served as the hosts of the most recent example of a direct military confrontation between two Great Powers, when Savam and Lutoborsk forces clashes directly during the Rastovid War of 1999-2003, the last of the so-called Garden Wars. Since the 2003 settlement at the Gattam Accords, the situation in the Rastovid Confederacy is more or less stable, although a number of unresolved questions remain and Savam has increasingly focused its attention on Lutoborsk as a rising threat, which helped steer the détente with Odann. Fossil fuels also played a central role in the late 1980s Borean War with Kiy. Further south, Savam is less directly involved in the affairs of Domradovid Joriscia; it engages there mostly via the proxy of Settecia, a significant strategic and trade partner which is primarily a client of Savam's ally Zeppengeran.

The Occident

- Ascesia

Meridion

In Lestria Savam's main client is the Baygil Empire to which it provides technological and strategic support in exchange for assistance with Savamese corporate interests in the Lestrian Neutral Zone and the continued recognition of the port-city of Heihai on the Baygilene coast as a Savamese direct overseas possession.

This relationship with Baygil is the source of some annoyance between Savam and Zeppengeran, with the latter being generally unfriendly to the Baygilenes due to their antagonism to and competition with Zepnish Machtbunds.

Military

Military tradition has a long established history in Savam, stemming from the armies of the various Sabamani Empires that carved vast domains in pre-Secote Messenia. The current imperial army was founded the same year as the empire (1798), and underwent its large major reorganisation at the end of the Long War. It is currently divided between the Imperial Army, the Imperial Navy, the Imperial Airforce, the Imperial Aerospace Division (an Airforce’s offshout), the Imperial Militia (a military police force with civilian law-enforcement capabilities), and the Imperial Guard (both a ceremonial and special operations rapid reaction force). The military’s four main branches (army, navy, airforce and militia) are further divided into metropolitan and colonial corps. At any moment of the year, enlisted soldiers from all branches including both conscripts and career soldiers, totals approximately 3.17 million.

Savamese citizens share a close relationship with their army, which is an essential part defining the Savamese identity. Undertaking the recurrent national service is required to avoid being politically ostracised; for most people, it consists in 20 months of initial conscription usually before age 30 and several weeks every year until a citizen reach their 50s. The doctrine of national readiness is essential for the government; even if a large-scale war with millions of conscripts seems unlikely in the 21st century, the national service is so entrenched in the national collective consciousness that it would be difficult to reform it more than marginally. The Savamese military also plays a direct role in the political system with its representative in the Council of the Chancellorship.

Recent or current foreign and overseas deployment of the Savamese military include: the Baseriote Insurrection (Transvechia, 2004-current), Operation Fluvius (the Rastovid Confederacy, 1981-current), thwarting the Phouspet coup attempt in Saint-Calvin (2006), Third Felicia War (Serania Major, 1996), the Rastovid War (the Rastovid Confederacy, 1999-2003).

Overseas territories and colonies

Savam is often perceived as a continental land power due to its important role in inland Messenia and Inner Joriscia and because of its limited access to the global oceans compared to other Great Powers: getting out of the Arcedian Sea requires crossing waters largely controlled by other powers. Nonetheless, the empire, and some of its predecessors, have managed to build a sizeable navy and maintains significant colonial holdings (and colonial corporations) in the western hemisphere to compete with other Great Powers for resources (in the Seranias) and control of markets in Ascesian and Lestrian states. In total, the Savamese overseas possessions span 13.9 million square kilometres, with a population of 51.4 million1.

Savam’s principal non-colonial overseas territory is the island of Doreysne in the Medius Sea, which was seized from Siurskeyti in 1812 through an opportunistic campaign during the Summer War. The island is a very strategic location for Savam, which has based its efforts to maintain a certain naval power on it. It provides an essential relay for Savamese ships travelling from Savam’s northern ports to Serania via the south-western route. Doreysne is not considered a colonial land in Savamese law; actually, there is a significant political movement both on the island and in the métropole for its elevation to statehood. Currently, the island is governed as an autonomous vice-principality similarly to colonial possessions, but with a greater autonomy versus the federal government than the latter.

Seranias

The Savamese colonies in the Seranias are organised in five vice-principalities, autonomous self-governing entities that depends directly from the federal government instead of member states; their exact degree of autonomy is determined by a number of factors. The most populated vice-principalities of West and East Felicia, as well as the vice-principality of the Isles and Victoria, enjoy the largest degree of autonomy thanks to their significant population and relatively developed economic infrastructure. On the other hand, the Great South is more tightly controlled by the federal government.

In all colonies, the Vice-prince is appointed by the Viceroy; in the most autonomous colonies the Vice-prince will govern alongside a government elected by the local population, organised along classical Savamese respublican parliamentary systems. Like the mainland states, the colonies are further subdivided into prefectures and communes. In some low-density areas, the requirements to have at least 5,000 citizens of voting age to form a commune has led to the formation of municipal areas extending over very large areas. Noble lands property laws govern a significant portion of the colonial lands.

Ascesia

The Savamese sphere of influence in Ascesia regroups several ut possideatur states under patronage, mostly located in the Serrinean peninsula, the largest (and most directly controlled) being Dodaristan; other states where Savam has influence are Nation 128, Sornastria, and Shacoont. Finally, the State of Yarin on Yarin in the Median Islands is also an imperial protectorate.

Like other Great Powers, Savam has heavily re-organised the political structure of Eastern Ascesia to bring it in line with Messenian-style interordinate relations. In those states, both the Savamese government and colonial corporations directly oversee aspects of the local government, education systems and economy alongside native structures (to various degrees). Although they are not members of the Savamese Customs Union, those states are in close relationship with it, with at least 3/4th of their exports and imports taking place with SCU members or associates. The Empire is also involved in more independent states through a number of interordinate organisations such as the Tarves Board or the Freta Mano Commission

Inner Joriscia

The Savamese sphere of influence in Inner Joriscia roughtly extends over the great north-western half of the Rastovid Confederacy. Although some of this is shared with Ceresoran interests, the Savamese have almost exclusive politico-economic control over three autonomous regions within the Confederacy. The provinces of the White River and Transturby have significant Sabamic populations (Kérates, Mégers), or Savamised West Secote inhabitants; Transturby directly borders Savam proper and has been colonised by Benovians. New Elmiesia does not have such Sabamic populations but its government and economic is under heavy influence by Savamese interests.

Scattered port-cities

Like other Great Powers Savam directly controls a number of port-cities alongside major traditional oceanic trading routes, such as the Great Belt. All are administrated as overseas prefectures. There are currently five such prefectures, three in Ascesia: Nosivangue in Nusileh, Sangin in Sornastria, and the multi-city Cinq-Ports in Dodaristan; one in Diothún: Port-des-Vents; one in Lestria: Heihai in the Baygil Empire.

Those ports are important pieces in a network that support transoceanic shipping, projection of military power, and worldwide telecommunication networks. There are many other ports scattered in Lestria and Ascesia where Savam has varied level of control through trade concessions and other similar arrangements with client polities or allies. However, given that those concessions are not directly administrated they are generally not considered to be Savamese territory; they do belong in the Savamese exploitation colonies nonetheless.

Colonial corporations

Savam's colonial corporations are mostly private, although the largest (by revenue) is a state-owned corporation, the Compagnie coloniale nationale (CCN) which is jointly owned by the federal and states governments; the other corporations are principally controlled by aristocratic interests. Savamese colonial corporations are mostly active in Inner Joriscia and Ascesia, and to a more limited extend in Lestria where they have declined in recent years because of aggressive Outer Joriscian competition.

Finance and economy

Overview

The Savamese economy is a heavily regulated free market, where the government plays a considerable role, endorsing economic dirigism in the form of state capitalism and some degree of economic planning. Private enterprise and competition is encouraged in areas that do not fall in the scope of the government's economic policy, or which are delegated through procedure such as affermage. Alongside this private sector, the federal government controls monopolistic corporations in strategic fields such as energy production and distribution, telecommunications, transports, the defence industry, etc., and can weight in other sectors via its financial clout. A pioneer in industrial development, Savam has a strong industrial sector; some of its most successful industries includes mechanical and electrical engineering, siderurgy, transports (from airplanes manufacturing to the shipping industry), and generally many high value-added industries, including mining and pharmaceutics.

Savam has a complex tissues of private and publicly-traded companies, ranging from immense polyindustrials to small businesses. The overall influence and economic role of the polyindustrial corporations is important, but not as much as compared to the omnipresent influence of Zeppengeran's Machtbunds. The aristocracy is very involved in the private sector through land ownership (with a specific fiscal regime) and investments in heavy industries, the finance sector, colonial business (trade and defence contractors notably), the agro-industry, and medias, inter alia. The majority of Savam's largest polyindustrials are owned by noble interests, allowing the upper nobility to retain a significant influence over the country's affairs. The federal government owns many corporations that have monopolies or quasi-monopolies in strategic sectors, which are either mandated by law or the result of intervention in market forces. On the other hand, it is common for the federal government to subcontract regalian activities to private companies through forms of revenue leasing. Approximately 30-40% of Savam's GDP comes from the public sector (in terms of GNP, significant private interests in colonial and colonial corporations reduces the ratio to about 20-25%). Economic interests owned by the country's royal houses are seen as instruments of the state instead of private companies, although they are not controlled by the federal government.

The Imperial Bank is the government dirigist spearhead, providing credit to government and private corporations and private citizens likewise, and taking participation in the private financial sector. Regulations impose that the government owns, at least, a blocking minority in all private financial institution; in effect the government is a few percent off majority ownership in most private banks and insurance companies (a constant source of tensions between the federal government and the aristocracy who otherwise controls the financial sector).

Customs Union and protectionist sphere

Savam, its colonies and its client states in Messenia and Ascesia fall under protectionist barriers to ward off undesired foreign competition, for example in low value-added production such as basic clothing. Internal (as in, inside the protectionist barrier) social standards competition is tolerated, although the Savamese government makes sure its clients are not going too far into social dumping (principally in Messenia proper, clients states in Ascesia operate with more freedom). Savam and its clients are linked into the Savamese Customs Union (SCU), where the Aurel is the principal currency in use (although not the only legal tender). Nevertheless, the borders are not closed: trade and foreign investments are welcomed, as long as national interest is not at stakes; the exact balance between protectionist and free trade, and justifications for each, is a recurrent debate in Savamese politics. Large corporations tend to favour protectionism in order to protect their interests inside the SCU from competition by similar foreign structures.

Luxury goods are well established Savamese exports, along high-tech manufactured goods. Nonetheless, because of the market depth provided by the SCU (for example, most lower valued-added goods are imported from Ascesian client states), the principal exchanges concerns commodities. Savam lacks many commodities that are necessary to support its industries, and cannot satisfy all the demand solely from colonies or client states; for example, half of the oil and natural gas consumed by the country is imported from outside the SCU (inside the SCU, the largest source is Transvechia). On the other hand, Savam is the World’s second largest producer of copper.

Despite a certain focus on internal demand, the Savamese government recognises that exchanges outside of the SCU are necessary to maintain a healthy economy. It must thus permanently adjusts its policies to balance protectionism and free trade, and negotiate with foreign powers. Savam principal economic partners are also its political allies. Zeppengeran and Helminthasse have entered free trade agreements with the SCU in the 1970s and 1980s, and similar arrangements have been passed with Agamar in the 1990s. Savam also has signed trade agreements of more limited scope with other countries in Messenia such as Elland or Brolangouan.

Agriculture

Savam’s location in the temperate fertile alluvial plains of Northern Messenia made it an historical agricultural powerhouse, virtually self-sufficient in modern days and always at the centre of a vast network of agricultural exports. Since the advent of the trans-continental trade routes in the 1st millenia BCE, Savam has been, alongside the region centred around Elland, the grain basket of the southern civilisations developping in a dryer climate. Its percentage of cultivated arable land is high compared to the Messeno-Joriscian average. About a third of the cultivated area falls under noble property laws.

Today, Savam has one of the largest agro-industry in the World, producing many different vegetal and animal foodstuffs for its internal market and exports to other countries. The most important crops are wheat, corn, sunflower, potato, sugar beet, canola and a wide variety of fruits (notably apple, peach, pear, grape, watermelon, plum etc.). Livestocks are diverse, ranging from many poultry species to cattle and pigs. Fishing is a substantial part of the Savamese agricultural sector, with many boats active in the ecologically-rich waters of the Fulvian Gulf. Quènie is more known for its production of domesticated molluscs such as mussels, oysters and scallops.

Fine foods are successful exports too, from wines of the southern Massif Cardussien to Lake Carles rogue noire. Nonetheless, by volume, Savam processed foodstuff principle export remain spirits, from liqueurs and eaux-de-vie based on fruits to grain spirits such as eau-ambrée (whisky).

Transports

Savam possess highly developed transport networks, sometimes with histories stretching many centuries. Its location at the interface between Inner Joriscia and Messenia, and its long civilisation’s history has made of Savam a well-traveled area early on. The many natural waterways of such rivers as the Gaste, the Génestre and the Védomagne were the first backbone of people and good transportation in Savam; artificial waterways construction go back to the Sabamanians of the first millennium BCE.

Today, Savam has extensive roads, railways and waterways networks. Motorways were built in the country starting in the 1970s and now links all the major population centres, extending outside of Savam in neighboring countries. It is supported through road taxes and tolls. Savam's railways are some of the most extensive in Messenia, and include a network of high-speed trains that was inaugurated in the 1990s and is currently undergoing a major extension. Intra-urban connections are also well developed with both underground services and tramway services complementing bus services.

The Savamese waterways network accounts for more than 30,000 km, including man-made canals, engineered rivers and naturally navigable rivers. Although many ancient canals are still in activity, the network was massively extended during the industrialisation of Savam, starting in the mid 19th century. Savam has several deep-water ports on its northern coast, at the terminii of the great rivers waterways: Lèz-les-Sablons and Jagues-Salins in Dordanie and Giscours in Quènie.

Ethnology & demographics

Ethnology

The empire’s majority ethnic group are the Savamese. As with most other ethnic classifications, the Savamese are more defined by adherence to common cultural values than biological variables, although a typical phenotype can be asserted in the population. The cultural framework that defines Savamese identity is relatively large. It has evolved from the earlier politico-religious foundations of Catholicism within the Cairo-Sabamic world to form a more distinct identity, sometimes termed the Savamese nation. In the 18th century, the Savamese found themselves in opposition to most of the other Sabamic Cairans through their adherence to the Cairan Reformation; the schism of Cairony was instrumental in establishing the Savamese as a distinct people from their Sabamic brethren. As a result, religion is still a major element in Savamese identity today. However, it is not the only defining factor. Loyalty to the Emperor, and general adherence to a cortege of perceived superiority, respopular or liberal ideals, and patriotism (especially expressed in the national service) are also important markers of Savamese identity. Furthermore, being Savamese also includes strong traditions of etiquette and codified interpersonal relations, as well as courting and marital behaviours. The heritage of the Sabāmanians is strongly claimed as part of the Savamese identity too.

Although the Savamese language is the empire’s official language, it is not strongly required to identify as a Savamese. Related languages of the Sabamic family are accepted, especially if they go together with a working knowledge of Savamese. However, in the last century there has been a slow shift toward an increase of the importance of language into the definition of cultural identity, notably due to the spread of Savamese-language-only mass media and primary education that improved widespread knowledge of the language versus local dialects. In particular, the Savamese government has used media to increase the prevalence of Savamese in neighbouring countries considered to be inhabited by subgroups of the Savamese people, in order to maintain and improve the connection between those groups and Savam, reinforcing in some case their desire for assimilation within the Empire.

The Savamese consider themselves to be an open nation. Indeed, when one is born a foreigner, it is possible to assimilate into the Savamese people by demonstrating adherence to their values, whatever one’s original culture and appearance. Any child educated in Savam (or in Savamese system abroad) can also call himself/herself Savamese.

Subgroups

The Savamese people is often defined both as the cultural-ethnic group and as a more overreaching notion, i.e. a "super" cultural group including several components and subgroups. Within that last definition, the "core" Savamese are those defined beforehand, speaking Savamese and of reformer confession, but other cultural-ethnic group are also deemed Savamese based on an arguably looser definition of what a Savamese is. Arguably, there is a significant overlap between this extended view of the Savamese people and any Sabamic people, though some Sabamic groups like the Astredans or the citizens from Tisana are never included in this enlarged definition; in effect, the extended view matches the North-western group of the Sabamic languages familly.

There are five accepted subgroups of the Savamese people that do not speak Savamese: the Bouescians, the Embute, the Samezeans, the Verborians, and the Transvechians.

Bouescians

The Bouescian people are the smallest of the subgroups found in Savam, as most of their population is located outside of the empire's boundary in Estologne in Brex-Sarre; in Savam propre most Bouescians are found in the south-western fringes of Dordanie (in Adaque). Their language, the Bouescian language is part of the small Sylvan subfamily of the North-Western Sabamic languages and considered somewhat intermediate between the Savamese dialects and Samezeau (especially the northern dialect). The Bouescian are readily perceived as being Savamese due to many centuries of inclusion in the realms, with their removal from direct Savamese control or influence only about 130 years old. Within the context of ethnic groupings in Brex-Sarre the Bouescians are categorised as Sarrois Savamese.

Embutes

The Embute-speakers found in Valdenois, Emilia, Saint-Calvin, Argevau, Rochardy, Brex-Sarre, and northeastern Elland, have long been accepted as part of the Savamese people. Indeed, Embute people have been subjects of the Savamese realms for many centuries and were largely included in the foundation of the Savamese Empire in the late 18th century (for those in Sarre and Emilia). The Embute dialect spoken in Etamps-La-Sainte had a significant influence on Savamese as a prestige dialect spread among the educated elites. Embute culture is also closely related to Valdenian culture, and the Embutes are largely reformers (although not in majority for those outside of Savam).

Samezeans

The Samezeans are the majority in Occois-Garde, as well as outside of Savam's boundaries in northern Cantaire and the north-western most region of Vallinia in Ceresora; broadly speaking in a region centred around the Twin Lakes. Savamese scholars classify the Samezeau language closer to Savamese than the Cantairean or Astredean languages in the Western Sabamic dialect continuum (Samezeau and Savamese are both part of the North-western group, respectively Occan and Dordanian subgroups, while Cantairean and Astredean are classified as South-western). The inclusion of the Samezeans in the Savamese people is less contentious than the Verborians because, like the Embutes, Samezeans have been part of the Savamese realms for many centuries and have influenced the formation of Savamese culture to a certain degree. For example, the well-known intellectual centre of Poignes, now within Dordanie, has been a Samezeau-speaking city for most of its history: many of the founding documents of Orange Revivalism and the La Roche School were written in medieval Samezeau (for those not in Late Sabamic).

Verborians

In the east, the Verborian-speaking people of Benovia are also perceived as part of the Savamese people; the broader definition also includes all Verborian-speaking people, who are mostly found in Ceresora and to a smaller degree in Transvechia. However, this identification is contentious and has been at the centre of debates about identity for centuries. Prior to the 18th century the Verborian identity was not really seen as strictly separate as that of the Savamese, especially by the Verborians themselves; for example, they still shared the same national argan. However, the Cairan Reformation and subsequent Reform Wars led to a major schism between the orthodoxist Verborians ruled by the Bragoni dynasty and the reformer Verborians ruled by the Dordanian monarchy. With the majority of Verborians in the former category, this has helped creating a distinct sense of identity different from the Savamese people. However, the Verborians in Dordanie and Benovia who have converted to the reform have no doubt about their Savamese identity (the Benovians' Savamese-ness is actually instrumental in the claim that Verborians are Savamese) and so as a whole the Verborian people is still seen as a subgroup of the Savamese people, with the orthodoxist cohort considered "lost sheep" to be herded back to the community.

Transvechians

The Transvechians are found in north-eastern Dordanie, northern Benovia, and are the majority group in Transvechia. They speak several languages and dialects from the Sabamo-Aquilonial group, which is also part of the North-western Sabamic languages group, although Savamese is used as the common bridge language in Transvechia for historical reasons. Some of the local languages, such as Roménian, are quite close to Savamese. Similarly to the Verborians, prior to the era of the Reformation there was no strict separation between the Transvechians and the Savamese; in the early 16th century the whole of Transvechia had been integrated into the Dordanian hegemon's orbit and remained so for the next 250 years. There was a lot of cultural contact between Transvechians and Dordanians as people from both groups manned the colonisation front that moved eastward of Siletia and displaced the local Baseriotes and Hyperboreans. However, when the Reformation came the majority of Transvechians remained loyal to Orangism, and the Transvechians secured their political independence from Dordanie during the Transvechian Uprising War which ran concurrently with the Third Reform War. From their they started to build a separate identity, but this was dampened by the restoration of Savamese overlordship after the 1867 Settlement of Etamps-La-Sainte. Today, while the vast majority of Transvechians remain orthodoxists, one and half century of close cultural and economic integration have meant that the Transvechians are considered a natural part of the Savamese people to a larger degree than their Verborian southern neigbhours.

Regional identities

The "core" Savamese ethnic group can be further subdivided into regional groups, principally differing on folk culture, local customs, and local dialects. Some of the prominent subgroups are the Dordanians and Valdenians, forming a so-called Dordano-Lacustrian cultural group, and the Quenians. The standardised Savamese language derives from the Dordanian dialect of the Dordanians; the Dordanian dialect is also described as the Gastian or the Riparian dialect since it extends in all Lower and Middle Gaste, including Brocquie. The Valdenian dialect is distinct from either Dordanian or Embute but influenced by both (notably because Embutes were in majority in Valdenois for many centuries before the break-up of Valdenois at the Treaty of Ráth). In Quènie the main local dialect is the Quenian dialect (also known as the Arcedian dialect), alongside the Gerssian dialect which is spoken around the Gersse river; the latter is influenced by nearby Daelic languages in Odet. The use of local dialects has no official recognition in Savam and has been declining quickly since the advent of mass media and standardised primary education. Nonetheless, millions continue to use them everyday alongside Savamese, especially in rural areas.

Non-Sabamic minorities

The Squades are the only non-Sabamic minority in Savam. They are a Daelic people living in the Est-Odet région of Quènie. Even if they are not Sabamic, the Squades are generally accepted as equals to other Savamese citizens. Their culture show strong Savamese influences and overlaps, and a large majority of Squades are reformers. However, monolingual and/or orthodoxist Squades are having more difficulties being accepted as Savamese. In case of language, this is despite the recognised regional status of Squade in Est-Odet.

Savam has small minorities of other non-Sabamic people spread throughout the empire, who are usually modern economic migrants. Most are West Secotes and North Secotes migrants from Savam’s sphere of influence in the Steppe. Non-Savamese monolingualism is getting rarer, as compulsory primary education in Savamese has been in force in all states since the end of the Long War. In 2011, approximately 25-30% of the empire’s population spoke a different language than Savamese (or a Savamese dialect) at home, but most of those were Sabamic languages. If counting only non-dialectal Savamese, about 55% of the population is speaking a different language at home, but there is a significant overlap with dialectal speakers that use both standard and dialect interchangeably.

Savamese Phenotype

The typical phenotype associated with Savamese is similar to the one found in northeastern Messenia and northern Inner Joriscia, not always very differentiated from the Secote stereotype: light-coloured skin and eyes, and a large incidence of blonde hair. Actually, Savam is one of the World’s country with the highest proportion of blonde people, estimated at up to 55%. Red hair are present in about 5–7% of the population, to compare with the worldwide proportion of 1–2%. Eyes colouration goes from grey to green, through blue. Dark eyes, anything darker than an olive skin and hair colours darker than auburn are generally perceived as exotic as they occur naturally in Savamese population very rarely.

Demographics

With a total population of 168 million (2017 estimates), the Savamese Empire is by far the most populous nation in Messenia and is second only to the Lutoborsk within the civilised world; the average population density is 238 inhab./km², which is in the high-end category for large developed countries. Indeed, the Savamese territory is mostly composed of fertile well-developed plains, allowing to support such a large population. Historically, the Savamese realms have always been a developed region: one of the principal grain basket of Messenia, it was already densely populated during the High Antiquity; in 1700 CE, the population within modern borders is estimated to have been 25 million, already the subcontinent's largest at the time. The empire's population passed the 100 million threshold in the late 1940s. A further 22 million live in the colonies in the Seranian hemisphere and the Median island of Doreysne.